- The well scene with Yaakov and Rachel is telling.

- First, it is a prime example of the general rule that in the Torah, our heroes are strong and our heroines are beautiful. Why is that? Aren't we supposed to focus on the internal?

- Also, note the reversal from Rivka's scene, where she diligently serves not only Eliezer but his camels. Over here, Yaakov not only serves Rachel and her sheep, but provides a service to the rest of the shepards as well.

- This is a great example of the necessity of תורה שבעל פה. In a sefer Torah, which has no nekudot, the fascinating if difficult to understand kiss between Yaakov and Rachel could be nothing more than him serving her water (וישק).

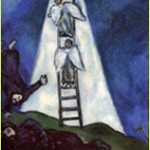

- The מלאכים that appear for the first time in Yaakov's dream, are a turn to the supernatural which is somewhat unusual, though not totally unheard of, for ספר בראשית. Note that they seem to resurface a few more times - at the end of the parsha (32:2) and into the beginning of וישלח, and are referenced famously in Yaakov's ברכה to מנשה and אפרים. Why did Yaakov need / merit this miraculous protection more than Avraham or Yitzchak? When does Hashem protect us directly and when does he use an angelic intermediary?

A place for Ma'ayanot Judaic Studies Faculty and Students to reflect and dialogue about Judaism. Please send all comments & questions to besserd@maayanot.org. Now check us out on Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/pages/Why-aanot/158509820897115

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Parsha Questions - Vayetze

Sorry so late:

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

29th of November

Here's a great video about the significance of the 29th of November. Enjoy!

Another fun fact - in Israel, this day is considered so important in Zionist history that there are streets named after it - like this one in Katamon:

Another fun fact - in Israel, this day is considered so important in Zionist history that there are streets named after it - like this one in Katamon:

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Thanksgiving and Torah Values

In the NY Times Health section yesterday, there was an interesting article about how gratitude actually makes people healthier, how exactly to define gratitude, and strategies for cultivating "an attitude of gratitude" (including religion). A lot of what the article says is in line with classical Torah values as expressed in ma'amarei Chazal. Check out the article. What do you think?

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Means and Ends

To me, one of the most inspiring things about our Torah is that it does not hide the flaws of its heroes. Quite the contrary: it seems to emphasize them. What is so inspiring is that these flawed humans are our heroes, our role models and our tzadikkim not only in spite of their flaws, but perhaps even because of them. We cannot use the excuse, "I'm only human! What does Hashem expect of me?" We are only human, we make mistakes. But that doesn't exempt us from aspiring to being like our Avot and Imahot. They too were human. If they could be tzadikim, then what is our excuse?

In Parashat Toldot, we find two episodes that are very troubling on many levels: Ya'akov's obtaining of his b'chorah from Eisav and his obtaining the brachah of the b'chor from Yitzchak. The former seems to involve some level of inappropriate pressure, while the latter seems to involve deception.

In the case of the b'chorah sale, I have always wondered more about Eisav and the omniscient narrator (Hashem as author) than about Ya'akov. Eisav comes in from the field and says to Ya'akov:"Hal'iteini na min ha'adom ha'adom hazeh ki ayeif anochi," and then the Torah states, "al kein kara shmo Edom."

Here are some questions for thought and discussion:

1. The word "na" seems out of character for Eisav. Eisav is an "ish sadeh"; this means not only literally an "outdoors" kind of person, but someone who is very rough, without the polish and manners of someone who is like Ya'akov "ish tam". He is more likely to demand than to say, more likely to declare "Gimme! Now!" than "Please ladle out for me." It is this character inconsistency that leads some to understand the word "na" as "raw" (another translation) and to say that Eisav was so uncouth that he would rather eat raw soup than wait until it's ready. But what if Eisav really did say "Please"? How does this affect our perspective of him?

2. Why does Eisav repeat the word "ha'adom"? Eisav is saying "Give me (please?) that soup that soup." What is it about "ha'adom" that requires emphasis by the text? Is it just that he's very very hungry, or is there something more significant about the repetition?

3. When Eisav is born it states: "Va'yeitzei harishon admoni, kulo k'aderet sei'ar"--he is identified as red from the moment of his birth. Why is he called "Edom" because of his request for soup rather than because of his coloring? In addition, why is Eisav so connected with the color red?

4. Finally, I will refer to a shiur that I once heard fom Dr. Aviva Zornberg, a very noted Tanach scholar. She asserted that what we learn from Ya'akov (and Yoseif) is that sometimes it IS okay to lie. (You have to be at the level of Ya'akov to know WHEN.) What do you think--do the ends (fulfilling a nevu'ah, fulfilling the legacy of Avraham) ever justify the means (deception)?

Happy thinking and discussing!

Shabbat Shalom!

Mrs. Leah Herzog

Is Thanksgiving Kosher?

My Gemara class today raised the question of Jews celebrating Thanksgiving. It is in fact a real halachik issue with varying opinions. See here for a comprehensive article on the subject by Rabbi Michael Broyde on the subject. His summary of the approaches (kudos to Rachel Olshin who told the class about the Rav's practice of ending shiur early).

In the end, Rabbi Broyde himself concludes that:In sum, three premier authorities of the previous generation have taken three conflicting views.

Rabbi Hutner perceived Thanksgiving as a Gentile holiday, and thus prohibited any involvement in the holiday. Rabbi Soloveitchik permitted the celebration of Thanksgiving and permitted eating turkey on that day. He ruled that Thanksgiving was not a religious holiday, and saw no problem with its celebration. Rabbi Feinstein adopted a middle ground. He maintained that Thanksgiving was not a religious holiday; but nonetheless thought that there were problems associated with "celebrating" any secular holiday. Thus, while he appears to have permitted eating turkey on that day, he would discourage any annual "celebration" (50) that would be festival-like.

This article has so far avoided any discussion of normative halacha. Such cannot, however, be avoided, at least in a conclusion. It is my opinion that this article clearly establishes that: (1) Thanksgiving is a secular holiday with secular origins; (2) while some people celebrate Thanksgiving with religious rituals, the vast majority of Americans do not; (3) halacha permits one to celebrate secular holidays, so long as one avoids doing so with people who celebrate them through religious worship and (4) so long as one avoids giving the celebration of Thanksgiving the appearance of a religious rite (either by occasionally missing a year or in some other manner making it clear that this is not a religious duty) the technical problems raised by Rabbi Feinstein and others are inapplicable. Thus, halacha law permits one to have a private Thanksgiving celebration with one's Jewish or secular friends and family. For reasons related to citizenship and the gratitude we feel towards the United States government, I would even suggest that such conduct is wise and proper. It has been recounted that some marking of Thanksgiving day was the practice of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, thus adding force to our custom of noting the day in some manner. Elsewhere in this article it is recounted that Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik would reschedule shiur on Thanksgiving day, so that shiur started earlier, and ended earlier, allowing the celebration of Thanksgiving. It is important to note the Torah study was not canceled, or even curtailed. Rather, the day was rearranged to allow for a full compliment of Torah, hand in hand with the requisite "civil celebrations." That too is an important lesson in how we should mark Thanksgiving.With that lesson in mind, I encourage you all to join us for Black Friday Shiur, this Friday. אנו משכימים והם משכימים...

Torah learning must be an integral part of what we do, and how we function. Sometimes, because of the needs of the times or our duties as citizens, we undertake tasks that appear to conflict with our need to study and learn Torah. But yet we must continue to learn and study. Thus, Rabbi Soloveitchik did not cancel shiur on Thanksgiving. We, too, should not forget that lesson. Torah study must go on.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Parsha Questions - Chaye Sara

- At Mishmar last week, Mrs. Kahan discussed the Rashi in this week's Parsha quoting the Midrash that the reason the death of Sara is adjacent to the akeida (even though it really isn't) is because after the Satan told her the news of Avraham offering Yitzchak as a korban, her soul "flew away" and she died. We saw many versions of the story in different Midrashim with fascinating differences. At the end of the evening, we started debating how Sara would have reacted had she been the one to be commanded to sacrifice Yitzchak. I thought that she would have done it, but we were pretty evenly split. What do you think?

- See here for a post on my favorite biblical character who's not actually biblical. I think she's fascinating and ripe for historical fiction (and I still think the name is cool).

- Chazal note the extended retelling of Eliezer's story in such great detail and comment that "יפה שיחתן של עבדי אבות מתורתן של בנים" - that the idle chatter of the servants of our forefathers is more precious than the teachings of their children. What on Earth does that mean?

- We see that Rivka is given the choice whether to go with Eliezer and marry Yitzchak or not, and she chooses to go, despite never having met Yitzchak. What do you think went into her decision making process (let's assume just for the sake of discussion that she wasn't a toddler).

- Finally, when she does get to meet Yitzchak he is waiting out in the field when she and Eliezer return because Yitzchak had gone "לשוח בשדה" - to converse in the field. Chazal take this phrase to refer to Tefila, and assert that this is when he founded תפילת מנחה. Can you think of any connections between מנחה and יצחק?

Lots to think about and react to this week - let's try to include some non-verbal feedback this week.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Sneak Preview - From the Stream

This week's Dvar Torah:

Let us start off with a number of questions.

· אברהם found out that he and שרה were going to have יצחק at the end of לך לך. Yet, three days later, the מלאכים came to tell him the exact same news with שרה overhearing? Why was it necessary for Hashem to tell either of them, let alone twice, of יצחק's pending arrival? Why couldn't they find out the way that everyone else does?

· If שרה's נבואה was greater than אברהם's, why was he told directly by Hashem & she through a מלאך (who wasn't even talking to her!)?

· Why did Hashem reprimand שרה for her laughter, when אברהם also laughed when he was told they would have יצחק? Rashi (based on תרגום אונקלוס) explain that the laughter of אברהם expressed joy, while שרה’s was cynical and doubtful, but why would that be? And even if it were true, אברהם heard the נבואה from Hashem. שרה heard the rantings of three Arabic nomads. Why would she be expected to take it seriously?

· שרה’s reaction is completely irrational. רש"י (יח:ח) tells us that the bread that she prepared was never served because “פירסה נדה” at the age of 89. With theנס process already in motion, why would her reaction be so skeptical? Once her body was miraculously rejuvenated, is ואדני זקן that much more of an obstacle?

It is well known that each of the אבות and אמהות embodying a certain מידה, which means not merely a good quality that they had, but a theological approach as to the proper way to serve Hashem. When we say that אברהם was an איש חסד, it means that he was active, externally focused in his עבודת ד'. Perhaps it also refers to a degree of spiritual optimism. We know that שרה personified גבורה (like her son יצחק). Maybe that implies the reverse. Based on the story in the Midrash, an early if not initial exposure to G-d (or at least His supernatural miracles) for both אברהם and שרה was the story of the כבשן האש. אברהם stood up for Hashem and was miraculously saved, שרה watched her father הרן do the same, and be burnt alive. Maybe this helped foster within each of them differing approaches to נס. To אברהם, anything was possible. When faced with a seeming contradiction – G-d’s promise that he would be the father of a great nation and his childlessness into old age, or even the same promise against the commandment to sacrifice יצחק – he knew that his is not to reason why, and that Hashem can make it right in the end. שרה on the other hand dealt with the practical, and was emotionally reluctant to rely on נסים. Therefore, when her child-bearing years passed with no children, she assumed that the ברכה would be fulfilled through ישמעאל, but never dreamt that she would still be destined to be the mother of this nation.

This is not a value judgment. שרה’s approach was not necessarily worse than אברהם’s, in fact sometimes her spiritual pessimism was proper. When ישמעאל was not turning out as planned, אברהם could only see his potential. It was שרה and her pragmatism that correctly recognized him באשר הוא שם – as he was – and Hashem explicitly told אברהם to concede to her superior judgment.

A נסיון (test) is designed to test the subject in his potential area of weakness. Of course had שרה received the news of יצחק’s impending birth in the same way as אברהם she would have reacted as he did. Perhaps שרה’s נסיון was to recognize the possibility of נס. True, she heard the news from less than reliable sources, and had no obligation to believe it. But what Hashem did expect was that she not dismiss it out of hand. “היפלא מד' דבר” ? Hashem’s words of rebuke explain שרה’s misstep. By cynically ruling out a miraculous conclusion to her story, שרה falls short of G-d’s expectation. This is not to say that שרה was a spiritual failure or any less than the אם ישראל we know her to be. Yet, the תורה is clear that Hashem is upset with her, so our job is to figure out why. The above may be a step in that pursuit.

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

In Memory of Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, ob”m

I was saddened to learn of the passing of Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, ob”m when I waked into shul today for Mincha. Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was the Rosh Yeshiva of the Mirrer Yeshiva in Yerushalaim, the largest yeshiva in Israel, and one of the largest yeshivot ever, with over six-thousand students. The Mirrer Yeshiva, amongst so many other yeshivot, was one of the great yeshivot in pre-holocaust Europe, unlike most of them however, the Mirrer Yeshiva still exists today, not only in Yerushalaim, but also in Brooklyn, NY and in branches throughout Eretz Yisroel.

Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was an American born Rosh Yeshiva, a scion of an illustrious family of Torah giants. He is named for Rav Nosson (Nota) Tzvi Finkel (1849-1927), who was known as the Alter of Slabodba, or “Elder of Slabodka”, the founder the Slabodka Yeshiva, one of the great mussar yeshivot. Though Rav Finkel grew up to become the head of Mirrer Yeshiva, his formative years were spent in Chicago, far away from the yeshiva, which he would one-day lead for over twenty years. As matter of fact, one could say that his childhood years were spent about as far away as one could imagine from one of the most prestigious institutions in the yeshiva word today.

Although I never had the privilege of personally meeting Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, I did hear him speak on more than one occasion. Twice I heard him address the NCSY Summer Kollel- once when I was a camper and once as a madrich. On a third occasion, I had the opportunity to hear a parsha shiur from him on erev shabbat in his home.

Since Rav Finkel had Parkinson’s disease and it was difficult for him to travel, our entire camp loaded onto busses and made the trip to a banquet hall in Yerushalaim, where he addressed us. On one occasion, Rav Finkel began by asking the boys who amongst them was from Chicago; immediately, a whole bunch of hands shot up into the air. Next, he asked them who attended Ida Crown Jewish Academy, again, a handful of boys raised their hands, though fewer than the time before. He then asked them who went Ida Crown and played forward for the Aces, Ida Crown’s basketball team; this time only one hand went up- his own.

The Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel I saw when I was a teenager, was far from the boy I imagined growing up in Chicago. He was tall though, tall enough to be a forward, and I could see him towering over his opponents, but the man I saw in front of me was frail, his body was ravaged by a debilitating disease, which made it difficult for him to speak or even sit comfortably in a chair. I remember him clutching his hands and thrusting them between his knees, which was all he could do to keep them from flailing uncontrollably by his sides. I have been told that although his symptoms were quite severe, Rav Finkel’s condition could have been alleviated greatly, by medicines which were readily available. Apparently there were stronger medications, which would help lessen his pain and discomfort, but he refused to take them because he was concerned that taking them would prevent him from thinking clearly, and would negatively impact his learning and his ability to continue giving shiurim in the yeshiva.

As he was trying to give us an appreciation for who Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was, one of our camp rabbeim pointed out that many of the great Jewish leaders, both past and present, had distinguished themselves in different areas. Some roshei yeshiva were gedolim in Torah, some were gedolim in chessed, some were tzaddikim and gedolim in ahavat yisroel or middot tovot, but Rav Finkel was a godol b’yessurim- great because of the challenges and difficulties he lived with. He was an effective leader and maggid shiur, rebbe and rosh yeshiva, despite the obvious pain he had to put up with to simply hold a pen in his hand. He was great.

Though I must honestly admit that I do not remember most of what he spoke about when I was a camper, I do remember one thing- he spoke about faith in Hashem, and as he was concluding his speech he asked all of us to recite Shema together in unison, we did, but one voice towered over all the rest- his own.

Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was an American born Rosh Yeshiva, a scion of an illustrious family of Torah giants. He is named for Rav Nosson (Nota) Tzvi Finkel (1849-1927), who was known as the Alter of Slabodba, or “Elder of Slabodka”, the founder the Slabodka Yeshiva, one of the great mussar yeshivot. Though Rav Finkel grew up to become the head of Mirrer Yeshiva, his formative years were spent in Chicago, far away from the yeshiva, which he would one-day lead for over twenty years. As matter of fact, one could say that his childhood years were spent about as far away as one could imagine from one of the most prestigious institutions in the yeshiva word today.

Although I never had the privilege of personally meeting Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, I did hear him speak on more than one occasion. Twice I heard him address the NCSY Summer Kollel- once when I was a camper and once as a madrich. On a third occasion, I had the opportunity to hear a parsha shiur from him on erev shabbat in his home.

Since Rav Finkel had Parkinson’s disease and it was difficult for him to travel, our entire camp loaded onto busses and made the trip to a banquet hall in Yerushalaim, where he addressed us. On one occasion, Rav Finkel began by asking the boys who amongst them was from Chicago; immediately, a whole bunch of hands shot up into the air. Next, he asked them who attended Ida Crown Jewish Academy, again, a handful of boys raised their hands, though fewer than the time before. He then asked them who went Ida Crown and played forward for the Aces, Ida Crown’s basketball team; this time only one hand went up- his own.

The Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel I saw when I was a teenager, was far from the boy I imagined growing up in Chicago. He was tall though, tall enough to be a forward, and I could see him towering over his opponents, but the man I saw in front of me was frail, his body was ravaged by a debilitating disease, which made it difficult for him to speak or even sit comfortably in a chair. I remember him clutching his hands and thrusting them between his knees, which was all he could do to keep them from flailing uncontrollably by his sides. I have been told that although his symptoms were quite severe, Rav Finkel’s condition could have been alleviated greatly, by medicines which were readily available. Apparently there were stronger medications, which would help lessen his pain and discomfort, but he refused to take them because he was concerned that taking them would prevent him from thinking clearly, and would negatively impact his learning and his ability to continue giving shiurim in the yeshiva.

As he was trying to give us an appreciation for who Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel was, one of our camp rabbeim pointed out that many of the great Jewish leaders, both past and present, had distinguished themselves in different areas. Some roshei yeshiva were gedolim in Torah, some were gedolim in chessed, some were tzaddikim and gedolim in ahavat yisroel or middot tovot, but Rav Finkel was a godol b’yessurim- great because of the challenges and difficulties he lived with. He was an effective leader and maggid shiur, rebbe and rosh yeshiva, despite the obvious pain he had to put up with to simply hold a pen in his hand. He was great.

Though I must honestly admit that I do not remember most of what he spoke about when I was a camper, I do remember one thing- he spoke about faith in Hashem, and as he was concluding his speech he asked all of us to recite Shema together in unison, we did, but one voice towered over all the rest- his own.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Parashat Vayera - Morality and Sacrifices

This parashah is so rich and action-packed that I'm not even scratching the surface of doing it justice in this post. Try to get to shul this Shabbat to re-learn this parashah, or spend some time reading it this week. Vayera is probably familiar from elementary school, but you will approach it now with a more mature outlook, and maybe these or other questions will come to mind.

- Morality

Will You sweep away the righteous with the wicked? What if there are fifty righteous within the city; will You sweep away and not forgive the place for the fifty righteous that are in it? It is profane of You (chalilah lecha) to do this, to slay the righteous with the wicked, that so the righteous should be equated with the wicked; it is profane of you (chalilah lecha) -- shall not the Judge of all the earth do justly?! (18:23-26)

Avraham is basically saying to God: "You are not living up to Your own standards of morality. How can You do something which is unjust, when You are the Source of justice?" Putting aside Avraham's brazenness (why wasn't he afraid to speak to God that way?) his question seems paradoxical. If God wants to do something, isn't that action by definition good and just? How can one challenge God on the basis of justice while at the same time acknowledging (as Avraham does) that He is the basis of justice?

- Sacrifice

At the end of the parashah, Hashem tells Avraham to offer Yitzchak, the son He had promised Avraham, as a sacrifice. Avraham's willingness sets an example of sacrifice for his descendants for all generations. But when are we called upon to sacrifice in the same way?

Last week my family lived for four days without heat or electricity (we did have hot water though, B"H). Some of my kids missed school, they did homework by candlelight, and we all shivered at night. We were very uncomfortable, but I don't think that was sacrifice, because it wasn't for any greater cause. At the exact same time, a friend told me, schools in Be'er Sheva were cancelled for at least 3 days because of missiles coming from Aza. I think that was sacrifice, of comfort and daily routines, and it was for a greater cause - a life in Eretz Yisrael.

On the other hand, Avraham didn't actually have to give up his son. Other Jews throughout history have had to make that ultimate sacrifice. Avraham is praised because he was willing, but he didn't have to actually sacrifice. What of those who are not willing, or have no choice, but who actually do sacrifice?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)